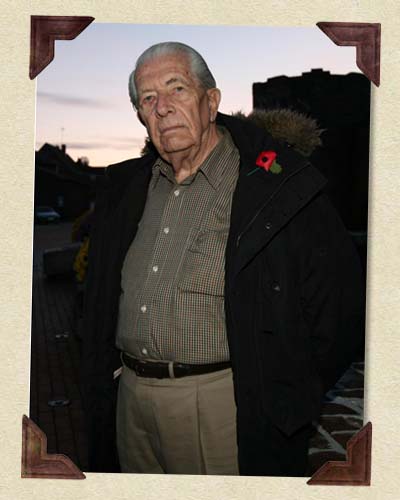

Major-General Gordon Maitland

Picture credit: Tim Anderson, Charles Miranda and the Daily Telegraph.

|

The United Services Institute presents

the Blamey Oration biannually in conjunction with the Field

Marshall Sir Thomas Blamey Memorial Fund. The oration

perpetuates the memory of Sir Thomas Blamey, Australia’s

highest ranking serviceman and, arguably, its greatest

soldier. In this oration, which marks the 54th

anniversary of the death of the Field Marshal on 27 May

1951, General Maitland reviews several controversial

relationships and events in Blamey’s career and, in seeking

to set the record straight, presents new evidence from his

own research on the Kokoda campaign.

I’m somewhat overwhelmed to see this

impressive attendance and I thank you all for making the

effort which, in a way, is a tribute to Blamey. The Blamey

Oration is intended to foster debate on key military and

strategic issues, but I feel that from time to time our

attention should return to the man himself.

As I note that many of you are my friends, I would

additionally thank you for your loyalty. I am thus

emboldened to make an unusual request

Would you please

expunge from your memories your past reading and list today

with a completely open mind. Why? You might well ask. |

Because to an extent you have been influenced

by writers who have allowed themselves to be influenced. They have

done well in bringing us splendid descriptions of terrain, events

and experiences, but some have produced conclusions beyond their

competence to make. Think of all that has been written about the

Kokoda Trail, including the published deductions, conclusions and

accusations. Yet you will fail to find any worthwhile analysis of

the conduct of operations.

Also, the influences which shape a commander’s decisions range

well beyond those that can later be identified by historians, some

of whom lack understanding of the culture of the army. Even when

comprehensive information is held, judgments will usually be

subjective – was a heavy penalty motivated by vindictiveness, or

was it simply warranted in the circumstances of the time? Early

in his career (1978) our eminent military historian Professor

David Horner wrote of ‘the necessity for a great deal of evidence

to ensure that reputations are not disparaged unfairly’ – but did

other authors read that? I think not!

Interpretation of Australian military events of sixty-odd years

ago was unfortunately shaped by the only first hand account of a

senior officer that was available for many years – General

Rowell’s 1974 autobiography. Not surprisingly, he presented

himself in a very favourable light and succeeded in tarnishing the

image of Blamey, who was no longer alive to provide his version –

not that he would have chosen so to do. The book was so santised

that it doesn’t mention Rowell’s removal of Potts from command of

the 21st Brigade.

Generals have special problems; they operate in a complex

political environment under unique stresses which can be fully

appreciated only by those who have had the experience. Whereas a

battalion commander is only accountable to his brigade commander,

General Blamey was accountable to his military commander, to his

Minister for the Army (Forde), to his Prime Minister (Curtin), and

to some other ministers. The media and subsequently the public

thought he was accountable to them too. There are those at lower

ranks who may choose to play politics, but general is the rank at

which soldierly forthrightness is not enough. Examples are not

hard to find. Consider the case of General Bennett. General

Sturdee, the Chief of the General Staff, advised Blamey that he

had misgivings about Bennett’s escape from Singapore, prompting

Blamey to decide to convene an inquiry. However, on that very same

day Bennett was commended by the Minister for the Army who,

considering himself senior to Blamey, was always loath to consult

him. In the circumstances, Prime Minister Curtin, obviously

concerned about public reaction, told Blamey to desist. Political

considerations will usually override military ones. Later, when

General Percival (Bennett’s commander in Malaya) criticized

Bennett’s departure from Singapore, Blamey was obliged to hold an

inquiry.

An American general once said: ‘The higher I climb the ladder

the more ‘arse’ people see to kick’. I accept that

responsibility has to be taken for errors and omissions; however

it is inappropriate that criticism of generals is usually freely

expressed without a sense of proportion being exposed.

Setting the Record Straight

Moving on to the actual topic, you will be aware that it is 60

years since the end of the Second World War. Last year various

ex-service organizations were considering what the focus of this

year should be. My friend (a member present here today) John

Allen, the son of famous Major General Tubby Allen, suggested that

it should be ‘Setting the Record Straight’. That is something that

hopefully, this talk may help to achieve – but in respect of Field

Marshal Sir Thomas Blamey, someone whom John Allen is unlikely to

have in mind.

To a minor extent, I am moved to do so by a feeling of guilt. I

was a 19-year old sergeant when Blamey flew into my brigade. It

took absolutely no time for the news to circulate that he had

brought ‘some grog for the officers’. It is incredible to look

back and remember how bitterly that news was received. To my

discredit, I joined in the condemnation of Blamey. It was a

reflection of how successful the media had been in poisoning

people’s minds about him. Quite obviously he couldn’t bring liquor

for the whole brigade and it was a courteous and thoughtful act to

bring it for those with whom he would be spending the night. He

was better received in places where officers had taken the trouble

to brief the troops: this was particularly so when Blamey was

being attacked by the politicians – a group not held in high

esteem by Australian soldiers. Indeed, soldiers had a lot for

which to be thankful to Blamey, as his consideration of them was

outstanding. At the very start of the war, he had told his senior

officers that he had selected them ‘because I think you will

look after the troops. This is my chief concern.’ I have

read criticism of even that praiseworthy comment, which indicates

the extent to which even thinking people have allowed themselves

to be prejudiced.

As this sad story progresses you will come to realize what an

undeservedly maligned person Blamey was. The media were the

principal offenders for two simple reasons – bad stories sell

papers; and Blamey’s peccadilloes set him up as an easy target.

About

Blamey

As this is about Blamey a brief description is warranted. He was

born near Wagga Wagga in 1884, one of ten children of a drover (he

obviously didn’t drove enough!). He became a teacher, and, as an

additional activity, he became a cadet officer. This led him to

the regular army and to his being the first Australian to pass

Staff College examinations. This took him to Quetta in India and,

when the Great War commenced, to appointment as a major on the

headquarters of the Australian Imperial Force’s (AIF) famous 1st

Division. He landed at Anzac at 7.20 a.m. on 25 April 1915, and

the official historian, Bean commended his work and bravery. He

went on to be a brigadier and Monash’s highly regarded chief staff

officer on the Australian Corps in 1918.

Subsequently he became Deputy Chief of the General Staff. In 1925,

he left the army to become Chief Commissioner of Victoria Police;

however, he served on in the militia. Although he was obliged to

resign from the police in 1936, he was Menzies’ choice in 1939 as

the commander of the 2nd AIF.

He had a unique presence, some say ‘radiating power’, and, in

1942, he was recalled from the Middle East to Australia to the new

position of commander-in-chief of the Australian Army, which he

steered to reach a peak of 14 divisions. It may surprise you to

know that 1 in 10 Australians served under him. Almost on his

death bed, he was appointed Field Marshal.

Blamey’s Dark Side

Blamey has his shortcomings: he drank heavily, but not so as to

detract from his work (one of his aides said he had ‘the body of a

bull’ and quite clearly he had incredible stamina), and he enjoyed

amorous adventures. When he decided ‘to party’, he would have no

compunction about doing so at a night club where he would be

rubbing shoulders with junior officers. But as Prime Minister

Curtin said to the press on 17 July 1942: ‘When Blamey was

appointed, the government was seeking a military leader, not a

Sunday School teacher’.

It did not help that Blamey, while Chief Commissioner of the

Victoria Police, had his name linked to a brothel raid and, later

had been forced to resign for having released information which he

knew to be untrue. Blamey placed loyalty very high in his rating

of personal qualities and his problems in the police force arose

from his being too loyal and

endeavouring to protect

the reputation of others.

Blamey’s ‘Achilles’ Heel’ was his complete disregard for what

others thought about him. His concern for his troops was

outstanding, but he never sought their approbation; he treated

Forde, the Minister for Defence, with contempt (but this started

with Forde, not Blamey); and completely neglected public

relations. But this was also his strength – in the Middle East he

fought so strongly (and loyally to his government and the

Australian Army) that he confided to his friend Major General

Burston that he was ‘the most hated man

in the

Middle East’.

Notwithstanding, both of his principal opponents, Wavell and

Auchinleck, held him in high regard – this according to Lord Casey

and Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke. Wavell referred to him as the

‘best soldier in the

Middle East’.

The Media

Returning to the media; their campaign against him started when he

fought with characteristic vigour,

but with characteristic tactlessness, to protect the Victoria

Police. Smith’s Weekly described the campaign as ‘the

most sensational ever conducted by the regimented Press against a

public official’. Famous correspondent, Chester Wilmot, added

fuel when Blamey received command of the 2nd AIF;

Wilmot referred to him as a ‘crook’, and circulated a story

of Blamey getting a commission from a laundry contract. Later, in

reporting the Greek campaign, he ignored Blamey’s farsightedness

in identifying the evacuation beaches, gave Rowell the credit for

the withdrawal and claimed that Blamey left Greece early

‘against the advice and in spite of pleading of his senior

officers’ – this despite General Wavell having ordered Blamey

to leave and General Wilson having dismissed Blamey’s protests.

Wilmot later raised rumours of Blamey profiting from picture

contracts and canteens, but never had any evidence for his

accusations. Indeed, in any rebuttal is needed, it can be found in

Blamey’s rejection of a very large sum of money to write his

memoirs, because, as he explained: ‘They would inevitably

damage reputations’. On 4 July 1942, Smith’s Weekly

went so far as to advocate firing Blamey.

At war’s end The Bulletin of 12 December 1945, finally extended an

apology to Blamey. It stated:

“He was watched continually by an unfriendly

press bent upon commanding his army for him and upon assuring that

he should not be accorded any of the privileges which commanders

normally are accorded by common consent in progress of keeping

their health and comfort.” It added: “[He] gave Australia equable

military leadership, and he did it without the unfaltering support

of Ministers, press or public. On the contrary, strong influences

were at work all the time to divide him from his troops, to

undermine his authority over them, even to incite their derision

of him”

Adverse publicity was such that only for a few

short periods was Blamey able to operate without the likelihood of

his being dismissed. However, he did make it and thus became the

Allies’ only commander who kept his command from the start of the

war to the finish.

The

Senior Officers

Sowing the rumours and the seeds of dissension was an incredible

collection of senior officers. Discipline is the cornerstone of

military forces yet this strange group obviously thought that

stopped with the troops. As distinguished historian Jeffrey Grey

wrote: ‘[A]t times, it must be wondered whether some of

Australia’s senior officers ever put as much energy into fighting

the Germans and Japanese as they did into quarrelling with one

another.’ Such rivalries were not unique to Australia; that

between MacArthur and the United States Navy was worse, and, if

reports be true, inter-service rivalry in Japan was even more so.

Most historians refer to staff corps versus militia rivalry but,

as senior officers sought to achieve their own advancement, both

the staff corps and the militia showed no reluctance to denigrate

their own. The so called ‘revolt of the general’ (regular and

militia) was aimed at Lavarack (a regular) and Bennett (a

militiaman). Senior officers should be ambitious, but it should be

a matter more of hoping to receive acknowledgment as a result of

performance, rather than agitating or, even worse, conniving, for

it.

It gives me no pleasure to talk in the following terms about a

former Chief of the General Staff, but Rowell’s behaviour towards

Blamey was appalling, and it is no less appalling that many have

glossed over it. When Blamey told Rowell (his principal staff

officer) that he had been ordered out of Greece, Rowell responded ‘I don’t believe you’. Rowell’s conduct permeated the

headquarters, and he later spread the story that ‘Blamey showed

the white feather and ran out of the country in a plane’. |

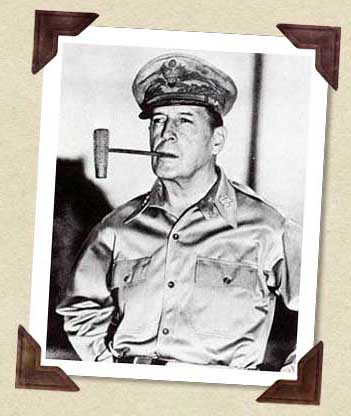

General McArthur

|

General Lavarack seized on that and so the damage to Blamey

spread. That Rowell continued his denigration of Blamey in

correspondence with Vasey was unpardonable disloyalty, as was his

later lack of balance towards Blamey in New Guinea. He used terms

like ‘crafty gangster’ and ‘evil cancer’ in

referring to Blamey. He wrote to another general (Clowes) that

‘I would never have believed a senior officer would have taken

what I said to him’. Yet, in his autobiography, Rowell accuses

Blamey of magnifying his remarks when reporting to the Prime

Minister.

Apropos Rowell’s accusation of cowardice; history makes it clear

that Blamey performed with great gallantry on Gallipoli, and there

is overwhelming evidence that his moral courage was second to

none. Quite obviously Wavell couldn’t afford to risk the capture

of Australia’s top soldier and Rowell’s inability to recognize

that situation and other incidents suggest that he lacked

politico-military awareness.

It was shrewd of Rowell to write his own biography for it

obviously dissuaded today’s critical military historians from

undertaking the task. Rowell makes much of the 25th

Brigade not arriving in Papua until 7 September 1942 (he wrote

that they ‘could have been in New Guinea in July or even in

June’), yet he would have been aware that Blamey was following

MacArthur’s wishes for the experienced 7th Division to

be kept for his future offensive operations; also on 21 August

1942 Rowell told Blamey that he didn’t want the 25th

Brigade; he only asked for it on 2 September, implying that up

until then he had seen his forces as adequate. His friend, Vasey,

saw him becoming ‘a bit full of himself’, and it is clear that

Rowell was intent on bringing Blamey down, showing no gratitude

whatsoever to his mentor who, in October 1939, had picked him out

as a lieutenant colonel, and had made him into a lieutenant

general by April 1942. The sheer total of Blamey’s achievements

proves Rowell to have been malignantly biased, and it is my belief

that critical study would reveal Rowell as a character quite

different form the victim popularly portrayed.

Blamey is accused of being a ‘hater’, but two months after the

Greek campaign he had sent back splendid competence reports

on Rowell and also on Bridgeford, who had also passed some

denigrating remarks.

Later both Generals Vasey and Robertson would go behind Blamey’s

back and cause problems for him as they endeavoured to advance

themselves, yet they trusted Blamey – everyone did. That was one

of the keys to Blamey’s success. Everyone respected his judgments;

they trusted him, so that there was wholehearted support for his

plans and the Australian Army found a confidence that played a

large part in its success.

Surely what MacArthur told Prime Minister Curtin on 17 July 1942

said it all. Curtin wrote:

“General MacArthur said that had heard much

loose talk from some people about General Blamey and he regretted

to say that much of it had originated from officers in the

Australian Army. Other Australian officers coveted the post of

Commander-in-Chief and had made representations against General

Blamey. He had also received anonymous letters on the subject.’

Having said that, MacArthur was playing his own

game.

General

MacArthur and his Cohorts

General MacArthur had been an abysmal failure in the Philippines,

but was theatrical, egoistic, and dedicated to his own self-aggrandisement,

never allowing truth to stand in the way. Many of MacArthur’s

press releases were not only distortions of fact, but fictitious,

prompting Jack Galloway, in his illuminating book The Odd

Couple, to dub them ‘Ripping Yarns’. When General Eisenhower

(later U.S. President) was asked whether he knew MacArthur, he

replied: ‘Yes, I studied drama under him

for some years.’

Although Australians in senior positions held prudish reservations

about Blamey, they were completely unconcerned about MacArthur,

whose private life was scarcely less sullied; and who turned a

blind eye to his senior American officers not only living with

Australian mistresses but putting them on the payroll, which

incidentally was met by Australia.

The government was without moral fibre, was frantic, and

was amateurish. It completely surrendered to MacArthur, handing

operational control of Australian armed forces to a foreigner and

abrogating Australian contribution to strategic direction –

incredible acts for which Shedden must share the blame. (Shedden

was the Defence Secretary, whom I will describe later). In an

historical article, on 6 December 1972, the Sydney Morning Herald

put the government’s sycophantic approach to MacArthur in these

words: ‘You take over what you need of

the entire resources of the country and we will have what you

leave’. |

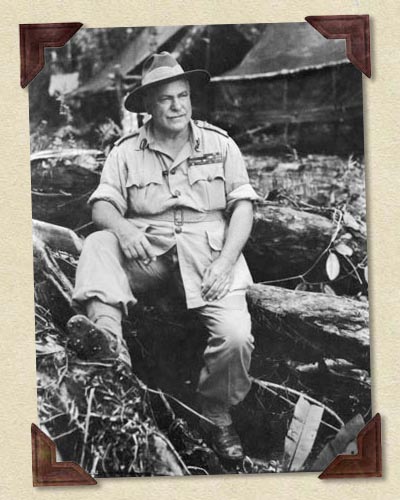

General MacArthur

General MacArthur

|

Unfortunately MacArthur was haunted by his failure in the

Philippines and his humiliating departure from Corregidor; as a

consequence he was fanatical about re-conquering those islands.

The United States Navy, on the other hand, was no less haunted by

the humiliation that had been inflicted on it at Pearl Harbour,

and also was bent on a redemptive crusade. It became a race, and

MacArthur was almost paranoiac in wanting to win the right to the

starting position for the liberation of the Philippines. His

consequent ruthlessness did not meet the standards Australians

look for in their leaders. Stephen Taafe wrote regarding the loss

of American lives at Wadke-Sarmi: ‘MacArthur sacrificed those

men not so much to win the war as to win his race with the Navy’.

In was in MacArthur’s interests to keep the Australian Government

under pressure, and he didn’t want any interference from Blamey

who seemed to be the only one to realize that MacArthur had no

interest in Australia’s future, only in his own. On the other

hand, he saw Blamey as far superior to the other Australian

generals and he needed both Blamey and the Australian Army in

order to achieve his aims. Being devious, he worked to retain

Blamey, but to curb him. In particular he was a master of public

relations and was determined that all good publicity would go to

himself.

Blamey served MacArthur loyally, but MacArthur would repay his

loyalty only so far as it suited himself. MacArthur was

responsible for Blamey being sent to Papua by Prime Minister

Curtin, to be the scapegoat in the event of an adverse outcome

there, and later he worked to delay Blamey’s return to Australia.

Later still, as American strength built up and reliance on the

Australian Army reduced, MacArthur sidelined Blamey as much as

possible ‘by stealth and by the employment of subterfuges that

were undignified and at times absurd’ – the official

historian’s words. However it must be conceded that MacArthur was

acting in accordance with guidance he had received from

Washington.

(CIC Prods. Note:

During the course of our research for our film we discovered proof

that General MacArthur lied to Prime Minister Curtin when he said

that it was the order of the US President and the US Joint Chiefs

that Blamey be sent to New Guinea. It was, in fact, MacArthur who

insisted Blamey go there, he asked only that President Truman and

General George C. Marshall to endorse his decision.)

Curtin had given MacArthur complete control over the media and he

took full advantage of it. All successes were attributed to

‘Allied Forces’, even if there had been no Americans there, and

MacArthur was presented as the successful general. Favourable

mention was never made of Blamey or other Australian generals; but

in this MacArthur was even handed – he never mentioned his own

generals either. It was the opposite when there was hint of events

not so favourable. MacArthur never accepted blame for anything and

was always quick to identify scapegoats. In Papua, it was the

Australians, notwithstanding that he owed everything to them. When

Shedden asked MacArthur why the beachheads campaign had lasted so

long he quickly blamed Blamey. It follows that while MacArthur

ensured that Blamey survived, his manipulation of publicity

tarnished Blamey’s image even further.

You will be aware that MacArthur finally got his comeuppance; he

was fired during the Korean War by President Truman, who observed

(and I don’t want the admirals here to smirk):

“I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the

authority of the President. I didn’t fire him because he was a

dumb son-of-a-bitch, although he was, but that’s not against the

law for Generals. If it was, half to three-quarters of them would

be in jail.”

Truman seems to have disliked generals even

more that Prime Minister Curtin.

The

Politicians

Before Curtin came to office Menzies was prime minister, and it

was Menzies who appointed Blamey to command the second AIF.

Thereby, Blamey was prejudiced in the eyes of the opposition Labor

Party. The trade union movement had already found against Blamey

because of his handling of strikes when Police Commissioner and,

as the movement was closely linked to the Labor Party, Blamey was

left with ground to make up when the party achieved government.

Needless to say, it was not Blamey’s style to endeavour to do so.

What is more, Curtin, the new prime minister, was a reformed

alcoholic and, as although puritanical, had been jailed for his

conduct as a pacifist – hardly the qualities that would appeal to

Blamey; or vice versa.

As Blamey stood head and shoulders above his competitors, Curtin

had no choice other than to appoint Blamey as Australian

commander-in-chief; however, it was a qualified appointment – the

Defence Department was given the responsibility for war policy,

and the War Conference which Curtin established, comprised only

himself, MacArthur and the manipulative Shedden. What was worse,

as mentioned earlier, MacArthur was given supreme command of the

Australian services and control of the media.

It is interesting to speculate how another general might have

fared, but the hierarchical system of the army was an anathema to

the Labor Party and it is unlikely that another would have been

received significantly better. Apart from a short period of two

years the Labor Party had been in the political wilderness, so

that it brought no experience to its new role. In addition, its

members had been opposed not only to military service but to the

military system, so that they lacked basic military knowledge –

this in the middle of a war with the nation in crisis. Little

wonder that The Bulletin chose to describe them as ‘a

government of novices’.

|

Blamey with MacArthur

Blamey with MacArthur |

In February 1942, Curtin earned a reputation for being an

outstanding wartime leader by standing firm against Churchill and

insisting on the return to Australia of the 6th and 7th

Divisions. In fact he had little choice; it is said that his Chief

of the General Staff had threatened to resign if he didn’t, and

some of his ministers (plus many others) were in a state of funk.

Not long after, when the news from Kokoda was at its worst,

Beasley, the minister for Supply and Shipping, in his agitation,

called out: ‘Moresby is going to fall. Send Blamey up there

and let him fall with it.’ At MacArthur’s opportunistic

suggestion and in ignorance of what a commander-in-chief’s job

entailed, that is exactly what Curtin did – sent him to Moresby.

If credit should go to anyone for how an ill-prepared and

dispirited Australia emerged from its greatest crises, it should

go to its battle winning soldiers, under the command of Blamey.

The government could scarcely have been more loyal to and

supportive of MacArthur; and consequently belittling of Blamey.

Even in January 1945, when suppression of news about the

Australian Army was a major concern, acting Prime Minister Chifley

would not approach MacArthur to loosen his stranglehold on the

media. Rather, an attack was launched at Blamey. This was the

government which had cut Blamey off from the media, yet it was

Calwell, the then Minister for Information, who told the media

that Blamey was to blame. It was all too much for Blamey, who, in

his best public relations manner, called him a liar! Not

withstanding, even Calwell was constrained to say: ‘The next man

to Blamey is like a curate to a bishop’.

MacArthur continued to bamboozle the government. When his Joint

Chiefs of Staff in Washington were reluctant to approve his

Australian-manned Balikpapan invasion, he sold it to them by

saying that cancellation would produce ‘grave repercussions

with the Australian government and people’. Yet, when Blamey

finally prodded Chifley to query MacArthur about the expedition,

the misleading answer that it had been ‘ordered by the Joint

Chiefs of Staff’ not only mollified Chifley but increased the

lack of confidence in Blamey.

The government was never wholeheartedly behind Blamey and the

continuing thought given to his replacement, even though it never

happened, was so well known that it detracted from Blamey’s

achievements which, clearly, the ‘government of novices’

had never paused to appreciate. There were always people, like

Shedden, volunteering comments on military matters, and the

government was only too willing to listen.

Tom Blamey in New Guinea |

The six months following 27 March 1942, when Blamey took up his

appointment, are revealing. The pre-war Military Board had failed

abysmally in preparing the Australian Army for war, and the

enormity of Blamey’s job was beyond imagination. The army had to

be restructured and reorganized and the arrival of American troops

in large numbers had to be absorbed. The AIF had been used to

being looked after by the British and the new need to be

self-sufficient created tremendous logistical, communication,

training, intelligence and security pressures; munitions also were

a major difficulty and every step had financial ramifications. In

addition, much was happening – air and submarine attacks, the war

in the north, and the never ending conferences (particularly those

demanded by the politicians). At the same time, Blamey was

commanding Allied Land Forces in which role he had to cope with

MacArthur’s paranoia about beating the United States Navy. Victory

in the 4 June Battle of Midway ended the possibility of an assault

against Australia, and attention was concentrated on New Guinea.

There, by the end of August, the Battle of Milne Bay had been won

and the only problem was the Kokoda Trail. Despite the

Australian’s steady retreat, the forces that Blamey had assembled

allowed no possibility of defeat, as Blamey assured the Advisory

War Council. The trouble was that the government’s inexperience

and alarm was too deep-seated and, when MacArthur expressed

concern, the politicians turned on Blamey.

The end result was, as mentioned earlier, Curtin’s 17 September

dispatch of Blamey to Port Moresby. Then, adding to that

disgraceful decision, Curtin told the media that he had sent

Blamey to New Guinea ‘to give him one final chance’. To

denigrate and undermine his commander-in-chief in that completely

undeserved way was shameful.

|

But even worse was in store when Curtin became ill, for Chifley,

Dr Evatt and others saw the army as a fascist organization and

Blamey as having the worst characteristics of that regime.

Finally, Forde, the Minister for the Army, vented his spite when

he gave little notice for Blamey in retiring him after the war.

Blamey, not to be outdone and ‘still the diplomat’, left Forde in

no doubt as to what he thought of him and his government – and

little wonder!

The

Civilian Bureaucracy

Firmly in command of the civilian defence bureaucracy was Sir

Frederick Shedden, Secretary of the Department of Defence from

1937 to 1956. He believed himself to be a military and strategic

expert, not by virtue of a six months stint overseas in the Great

War as a lieutenant in the Pay Corps, but by his attendance at the

Imperial Defence College.

He was a great admirer of the British way and was a disciple of

his British counterpart, Sir Maurice Hankey; so much so that he

was cleverly dubbed by some wit as ‘the pocket hanky’.

Hanky taught Shedden how to wield power behind the scenes. It was

Shedden who had been a strong advocate of the Singapore strategy,

despite a convincing criticism of it by the Australian Army but,

in the manner of MacArthur, he succeeded in putting the blame on

Britain when the Australian Army was proved correct and Singapore

‘came tumbling down’.

Shedden was one who swallowed MacArthur’s public relations ‘hook,

line and sinker’, going so far as to commend MacArthur’s inspiring

defence of the Philippines. He didn’t seek to talk to United

States High Commissioner Sayre, who was evacuated to Australia en

route to the United States, and who was embittered against

MacArthur. Perhaps Shedden knew on what side his bread was

buttered, for his later knighthood was probably due to MacArthur’s

suggestion to Curtin.

Professor David Horner’s biography of Shedden, Defence Supremo,

reveals him to be untruthful when it suited and dedicated to

‘blowing his own trumpet’. Indicative of how Shedden was; he

persuaded the government to request a Royal Air Force officer to

inspect and report on the Royal Australian Air Force without

telling the[Australian] Chief of the Air Staff.

It is intriguing that the Curtin government had MacArthur and

Shedden knighted, but not one Australian serviceman.

There is no denying that Shedden was a most capable and hard

working public servant, but like all in the senior bureaucracy, he

had an appetite for power. I give you that background so that you

may better understand when I tell you that he adopted the same

tactics as MacArthur to Blamey – keep him, but in an inferior

role.

General Wynter wrote of the civil staff:

“They take any and every opportunity to oppose

the Commander-in-Chief. This has been their attitude virtually

since November 1942 when Sinclair [the Secretary of the Army]

first started his intrigue for replacing the C-in-C by an Army

Council.”

Authors

It is interesting that authors have never

wanted to pick up the odd supportive remark about Blamey. For

example, were you aware that on Armistice Day (11 November) Blamey

would arrive at his office early, close the door, and live with

his thoughts until after 11 a.m.? Doesn’t that reveal a person

different from the one usually painted? David Horner is an

exception; in his valuable book, Crisis of Command, he

says: ‘Blamey always felt a certain loyalty to those officers

who had served their country long and well, and through no fault

of their own found themselves in situations that they were not

equipped to handle’.

Consider all the authors who have written about the Kokoda

Trail. They are numerous, and everyone maligns Blamey, but based

on what evidence? Remember that books, like newspapers, need to

‘spiced up’ to boost sales.

And what about the furore

over Blamey’s remarks to the 21st Brigade at Koitaki

after the decimated brigade was withdrawn from the Kokoda Trail.

Sadly, there is no proof of what Blamey said, but surely the first

source one would go to would be the commander of the brigade. Yet

no one ever asked Sir Ivan Dougherty. Ivan was my friend, and some

will recall my giving the eulogy at his funeral. In his

‘recollections’ he wrote:

“In other parts of this narrative I have

indicated that I am firm in my opinion that General Blamey’s

comments on the parade at Koitaki were given the wrong

interpretation. I was alert in carefully listening to what he

said.

He did use the term ‘rabbits’, but as I stood

on parade I did not anticipate that the men of 21 Brigade would

give his words the interpretation that he said the troops of 21

Brigade had ‘run like rabbits’. He said the Jap had animal-like

instincts. He said that while they stayed in their holes they

would shoot anyone who moved near them. He said it was like

shooting rabbits back home – we had to get them out of their

burrows before we could get them.

General Blamey said words to the effect that:

‘Brigadier Doughery has had troops under his command of whom he

has every reason to be intensely proud, and I know he will be just

as proud of the men of 21 Brigade’. Perhaps it might have been

better if he had mentioned the men of 21 Brigade first, saying

something like: ‘I know Brigadier Doughery will be intensely proud

of the men of 21 Brigade just as he has been intensely proud of

the men he has commanded previously.

In General Vasey’s war by David Horner, on page

220, it is written: ‘Back in Port Moresby MacArthur and Blamey

were in deep discussion about which formation to send, the 127th

U.S. Regiment, the 21st Brigade under Ivan Dougherty,

or perhaps the 41st U.S. Division from Australia.

Blamey told MacArthur that ‘he would rather put in more

Australians, as he knew they would fight’. MacArthur therefore

agreed to fly in the 21st Brigade.

This would most certainly appear to support my

contention that General Blamey’s address at the Koitaki Parade has

been misconstrued.”

Your Conclusion

It is difficult to know to whom to give

the last word. General Eather was one of the brigadiers

harried by Blamey on the Kokoda Trail, yet he wrote to his

parents: ‘To me it is disgraceful to think that a great

man who has done what he has for Australia in the last six

years should be open to attacks as he has been’.

Then there was General Morsehead. Curtin had chosen him as a

successor to Blamey ‘should unfortunately anything happen

to him’ [like being ‘fired’] Moreshead, when told, wrote

to Curtin: ‘I do sincerely trust that the occasion will

not arise. General Blamey is truly great Commander and it

would be a national calamity if he were to become a

casualty.’

Perhaps the most significant tribute was paid by MacArthur –

not in his memoirs in which he used the words ‘of highest

quality’ to describe Blamey, but by his 1948 action in

inviting Blamey to visit him in Japan, a very rare act of

gratitude completely out of character with MacArthur’s

normal conduct.

Today’s topic does not lend itself to spelling out either

Blamey’s successes or his mistakes. If your interest has

been whetted, then read David Horner’s biography. However,

it may help you to understand the man better if I mention

the following:

|

Field Marshal Sir Thomas Blamey

|

-

His whole military career was characterized

by his concern for Australian lives and interests.

-

Monash, who knew him as well as anyone,

described his mind as ‘prehensile’. For example, it was he who,

on Gallipoli, immediately perceived the potential of the

periscope rifle.

-

He and Monash conceived the first modern

battle – Hamel, which changed the conduct of war.

-

He thought and spoke about the future of

Australia. The Australian National University was one of his

brainchilds.

-

The steps he took on the health front were

quite outstanding. His seeking for advice; and willingness to

implement unusual measures beat malaria. He even brought Lord

Florey to Australia.

-

He was behind the emphasis on training and

the creation of training facilities which played a major part in

the success of the Australian Army.

The question you might wish to address is –

what motivated him? There are those who focus on his private life

and believe he lusted for power and the trappings that accompanied

it. Others believe he was a patriot, who stuck to the job,

despite his abominable treatment, because of his dedication to the

army and his determination to preserve it from mishandling by a

lesser person.

The subjective

judgement is one for you

to make; however whatever conclusion you reach, you must also

conclude that we were extremely fortunate to have had him; that he

deserved to be a Field Marshal; and that he didn’t deserve to be

so ill appreciated.

The Author:

Gordon

Maitland is a member of the Field Marshal Sir Thomas Blamey

Memorial Fund; and a past-president and current councilor of the

Institution. A former citizen-soldier, he joined the Army in 1944.

He eventually rose to command the 2nd Division and

become Chief of the Army Reserve, before becoming Regimental

Colonel of the Royal New South Wales Regiment. In civil life, he

was a senior executive of the Agricultural Society of New South

Wales. He is a noted military historian whose published works

include Tales of Valour from the Royal New South Wales Regiment

(1992); The Second World War and its Australian Army Battle

Honours (1999); and the two-volume The Battle History of the Royal

New South Wales Regiment, (Volume 1, 2001; Volume 2, 2002).

|